By now, we all know the story. A sex ring in Florida, circling the paedophile financier Jeffrey Epstein. An alleged encounter with a prince at Tramp nightclub in London, at the age of 17 — an allegation Andrew has always vehemently denied. A coterie of elites named in Epstein’s “little black book”, many of whom have so far remained unnamed. Virginia Giuffre’s story has been held in continual tension for years, with a feeling of something being unresolved clinging to each grim update. And then on Friday, she was found dead by suicide; she was 41.

While X has been about as level-headed as you might expect in the aftermath of her death (“So we don’t get the list and the people who talk about it keep ending up dead,” grumbled one post among many insinuating dark forces were at work), even the BBC couldn’t resist hinting at something sinister. “There will be suspicions the long shadow of Epstein’s poisonous misuse of wealth and influence has indirectly claimed another victim,” wrote its royal correspondent at the weekend. On Monday, Giuffre’s lawyer reported “no signs” that she had been suicidal, but dispelled any suggestion of suspicious circumstances. Whether we will listen is another matter.

This is a tale of shadowy elites and their unfathomable predilections; even the most sober readings cannot avoid the resonance of associations between presidents, princes and supermodels and a mega-rich paedophile. Its implications are inconvenient; it ensnares both Democrats and Republicans and gives the wacko acolytes of QAnon something to dribble over, pointing as it does to unseen networks of abuse at the highest levels of society, their bread and butter. Its twists and turns since Epstein first faced charges in 2006 have only enhanced the story’s conspiratorial flavour: shocking suicides, redacted documents and fallen heiresses are the stuff of a Le Carré novel at the best of times.

The Epstein scandal has long smothered the human tragedies that power it. Its principal players have become lazily drawn moving parts in a morality play about how power and money corrupt. Ghislaine Maxwell is the dazzling socialite with daddy issues; Epstein the predatory magnate with magnetic pull over the powerful; Andrew the bumbling spare, Mummy’s favourite. It is easy to forget the real lives — the “ordinary” ones — drawn into the orbit of the rich, famous and royal. When we do remember them, it is because they stray beyond the bounds of the perfect, media-trained victim.

Virginia Giuffre, or Roberts as they knew her, was such a case. She was an impressive woman: her family describe her as a “fierce warrior”, but rather than being radical she was unusually steadfast, consistent and credible during the Prince Andrew case. She filed a lawsuit against Epstein in 2009, before his notoriety and while he was still very much protected by his wealth. She was among the first to name Maxwell; she set up a charity, SOAR, to help other sex-trafficking survivors — this is where a reported $2 million of Andrew’s settlement was spent. In the years since, though, under unimaginable pressure, her composure unravelled. A divorce and custody battle over her three children — with domestic abuse allegations against her ex-husband Robert — was followed by a car crash earlier this month. Giuffre had posted a bizarre message on Instagram, accompanied by a photograph of herself battered and bruised in a hospital bed, claiming that she had “gone into kidney renal failure, they’ve given me four days to live”. The driver of a bus involved in the collision came forward to deny that it had been serious, alongside the local police force in Western Australia. Regardless of the medical specifics, when the story hit the papers, it was presented, with tasteful euphemism, as evidence of a very public mental breakdown.

Of course, there are legal considerations. Both divorcees were, it seemed, engaged in a tit-for-tat over restraining orders, not uncommon in Australian custody battles. The Instagram post was possibly a bid for contact with her children: “I’m ready to go, just not until I see my babies one last time”. But it was also a scramble for sympathy and comfort. After her death, a friend had pointed to the car-crash melodrama as a possible reason for her suicide: “Being discredited was one of the many things distressing her in recent months.” She was “deeply upset” about being mocked over the post, it was said.

One of many unspoken obligations of public survivors of sexual assault is never to succumb to your anguish. Though the post-MeToo media landscape has had plenty of practice covering victims, bearing evidence of the traumatic events of the past — mental-health woes, self-harm, identity crises — still seems to make them less credible, rather than more. The Mail wrote that “some of Andrew’s supporters” (a presumably small but mighty contingent) had labelled Giuffre a “fantasist” after the crash. Inconveniently, in that instant they did appear to have a point; her story did seem to have been exaggerated, and there was little evidence of her having been close to death.

Yet, the truth is that real-life victims do not retreat to a life of martyred perfectionism, softly delivering statements to gathered journalists with no more than one trembling tear. They are not animated courtroom exhibits. Female victims in particular draw the most sympathy when they are meek and withdrawn, never brash or erratic. They must be noble, saintly, virginal even — Joan of Arc — to be believed; the public cannot yet cope with complex backstories. Ten years ago, the Italian model Ambra Battilana Gutierrez was among the first accusers of Harvey Weinstein; she participated in an NYPD sting operation, wearing a wire and having him admit to groping and coercion. Because of her beauty pageant past and her entanglement with Silvio Berlusconi, her account was discredited in the American press. Would we see her testimony differently now? I don’t yet think so.

“Real-life victims do not retreat to a life of martyred perfectionism.”

We know, for example, that victims sometimes change their stories for reasons tied to the unknowable desire to forget. Wade Robson and Jimmy Safechuck, the lead accusers in the Michael Jackson documentary Leaving Neverland, are other imperfect victims who feature in smiling photographs with Jackson and even courtroom defences of him during his lifetime, only later reversed. Of course, the facts of such cases are for the legal system to decide — but there is much to be said about how unforgiving we are of the confusion and sometimes erratic behaviour associated with victimhood. These are not bulletproof testimonies, they are human ones. In truth, visible ruptures of messiness and despair are often scars, not red flags.

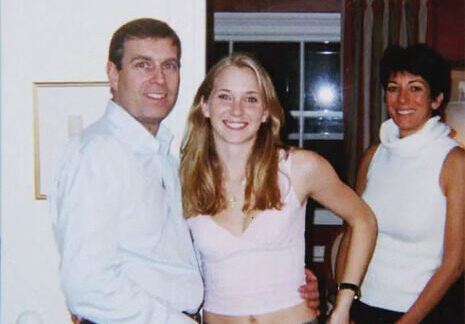

In Giuffre’s case, the dynamite was a picture of Andrew, Ghislaine Maxwell and the teenager taken in March 2001 by Epstein himself, at Maxwell’s London home. Now two of the people present in that room have killed themselves. The conspiracy theories will rumble into the next few weeks, ebbing away before the next chapter of this sad story: more documents might be released, more celebrities implicated, more dispatches from the “rat-infested” Federal Correctional Institution in Tallahassee where Maxwell is serving out her time.

In time, all that will remain is the sense that the ugliness of the worst excesses of the rich and powerful, normally so carefully hidden by intricate social protections, broke containment and spilled forth into public consciousness — and with them a curious, tragic woman who bravely told her story and then stopped being able to cope. This isn’t just a story about Epstein; it’s about the unseen depravity of those at the top of society — those bored of normal seductions, glutted on privilege, and the glassy-eyed girls they wave wads of cash at. If this scandal exposed political and financial East Coast elites, the P Diddy trial — due to commence on Monday — looks set to do the same to their West Coast entertainer counterparts. In that case speculation suggests that Justin Bieber, who appears to be going through his own public breakdown, is following in Giuffre’s tragic footsteps.

If we can learn something from the story of Virginia Giuffre, it is this: for the abuser we reserve the lowest possible standard of accountability; for the survivor, the highest possible standards of behaviour. Giuffre lived and died labouring under this irony. If her legacy is as an inspiration for other accusers to speak out, it’s worth remembering why so many cannot bear to: because in doing so, they submit to the strictures of idealised victimhood; fall apart and you may be disbelieved.