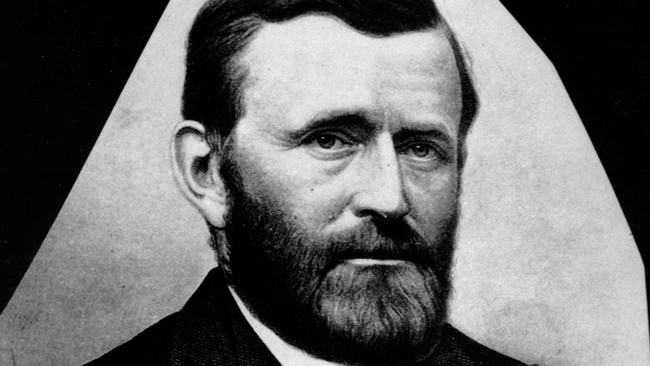

Ulysses S. Grant was the hero of his age, a brilliant general and a president with a lengthy list of accomplishments, especially regarding civil rights and the economy. In fact, in his own time, he not only reached celebrity status in America, but inspired the highest esteem in leaders and warriors around the world, from Europe to Asia.

“We all know how vast your influence must be, not only upon your people at home, but upon all nations, who know what you have done,” Prince Kung, son of the Chinese emperor, said to Grant when begging the former president’s advice and assistance in China’s domestic and foreign troubles. Whether he was in England, Germany, Thailand, China, or Japan, crowds gathered to see him and rulers felt privileged to meet him. Likewise, in America, many of his countrymen hailed his achievements, with Native American Indians and black Americans especially expressing respect for him.

Today, on this anniversary of Grant’s 1822 birth, I would like to share two stories to illustrate how beloved was the man who won the Civil War, reunified the nation, fought for civil rights, and brought prosperity and peace to America in spite of Democrats’ domestic terrorism and political machinations.

When Grant visited China, he was impressed by the industry of the Chinese and also worried by the unmerited racism exhibited against them by Europeans and, unfortunately, many Americans. He discussed with the Chinese viceroy the problem of “coolie” contract labor, whereby Chinese immigrants were brought to America only to work essentially as slave labor. He mourned that, having fought so hard to eradicate slavery, Americans were now seeing slavery in another form. Perhaps it was this extraordinary open-mindedness about the Chinese, and his willingness to see them as equal humans rather than inferior cattle, that made Prince Kung so eager to consult Grant.

Related: The Civil War Ended 160 Years Ago Saturday — Or Did It?

Kung evidently admired Grant, and he wanted the former U.S. president’s advice on modernizing and mechanizing China, on improving the lives of so many poor subjects in the country. Kung and Grant discussed the importance of railroads. “We have a country as large as China… We can cross it in seven days by special trains, or in an emergency in much less time,” Grant told Kung. “The wealth and industry of the country are utilized. A man’s industry in interior states becomes valuable because it can reach a market.” That was the vision Kung wanted to bring to China. But Kung also wanted to ask a favor of Grant — mediation with hostile Japan.

Praising Grant’s international influence, Kung brought up the disputed Loochoo or Ryukyu Islands and told Grant “whatever question you considered would be considered with patience and wisdom and a desire for justice and peace. You are going to Japan as the guest of the people and the emperor, and will have opportunities of presenting our views to the emperor of Japan and of showing him that we have no policy but justice.” What a remarkable compliment!

Grant ultimately discovered, as is usually the case in such disputes, that there were errors and good arguments on both sides, and he therefore tried to preach moderation, reason, peace, understanding, and objectivity to both sides, as he always had at home in America after the Civil War. One of his comments to the Japanese emperor is particularly interesting, as he warned against bringing European powers in to mediate: “European powers have no interests in Asia, so far as I can judge from their diplomacy, that do not involve the humiliation and subjugation of the Asiatic people. Their diplomacy is always selfish.” And unlike Grant, who strove through the second half of his life to overcome and fight racial prejudices, European leaders would always look down on the Japanese and Chinese as despised racial inferiors.

But Grant didn’t just have admirers abroad. When he returned to America after his international tour, his arrival in San Francisco was heralded by steam whistles from the city’s factories and canneries, by the city’s bells and the cannons of the fort and batteries. A flock of boats carried enthusiastic welcome committees (official and unofficial) out to meet Grant’s ship, and many more people thronged the wharves. He was greeted with cheers from packed crowds, all vying to see him and perhaps, for the fortunate few, shake his hand.

This was the man who won the Civil War and rebuilt the Union afterwards. The slaves he helped free and raise to citizenship, the veterans who followed him through hell on the battlefield, the voters his policies had enriched, all understood that to U.S. Grant they owed a debt of gratitude. He truly was the man who saved — and restored — the Union.

(Most of the information in this article is drawn from H.W. Brands’ “The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace.”)

The battle for our country continues. Join PJ Media VIP to support our work, and user the promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your VIP membership!