There has been some recent discussion again regarding the usefulness, limits, and problems of the well-known Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measure, which is often presented as a measurement of economic health and growth. For example, Dr. Patrick Newman presented a paper at the 2025 Austrian Economics Research Conference that partially dealt with the origins and problems of GDP. Following this, Dr. Newman discussed this further on a recent episode of the Human Action Podcast. This article seeks to review and discuss some key issues with the GDP metric, namely, GDP’s limited uses, the role of consumer spending, government spending and investment, and the other fallacies GDP helps perpetuate.

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) measures the total market “value” (prices paid) of all final goods and services produced within a country during a specific period. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) primarily estimates GDP using the expenditure approach, which tracks how much consumers, businesses, government, and foreign buyers spend on domestically produced final goods and services, subtracting the value of imports to isolate domestic production. While it aims to measure production, spending is used as a proxy.

Gross National Product (GNP) measures production by US citizens and businesses, both within the United States and abroad. GDP measures all production within the United States, regardless of who produced it—whether by the US or foreign entities. GDP became the US government’s preferred macroeconomic statistic in 1991, replacing GNP as the main measure of economic output. The statistic became popular, however, during WWII. The GDP equation is as follows:

C + I + G + (X − M) = GDP

C = personal consumption expenditures

I = gross private domestic investment

G = government consumption expenditures and gross investment

X = exports

M = imports

During WWII, and ever since, the GDP measure has been the most prominent. The debate about how to measure the economy had been ongoing, but economic analysis of the Great Depression, the emergence of Keynesian macroeconomics (that prioritize economic aggregates), and entry into WWII brought national income and product accounts (NIPA) to the forefront. Once adopted by the government for the wartime economy, the GDP measure became dominant, despite its shortcomings.

Limited Usefulness of GNP/GDP Statistics

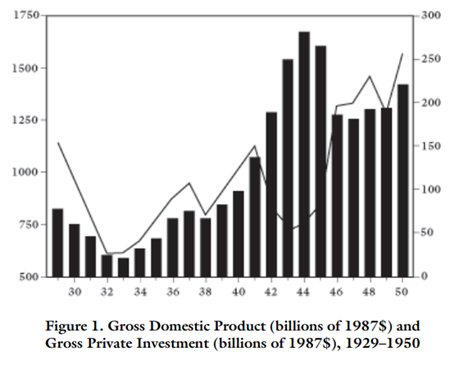

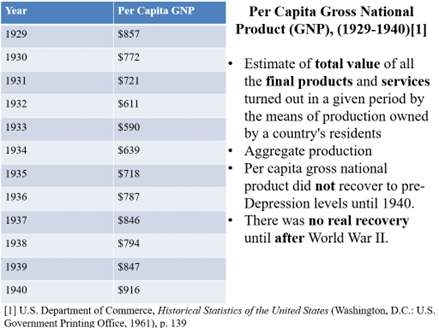

Before reviewing the problems and fundamental flaws of GDP, it is important to recognize that there is some limited usefulness to the measure. The usefulness can be used judiciously by the economic historian who recognizes the incompleteness and weaknesses of GDP as he examines limited historical data. Rothbard writes, “National product statistics, however, may be useful to the economic historian in describing or analyzing an historical period. Even so, they are highly misleading as currently used.” For example, we can look back to a certain period like the Great Depression/New Deal, examine GNP, and see that there was a lack of recovery despite these programs:

This is some interesting and historically helpful data, but we have to recognize that it does not give us the complete story. What is crucial is sound, consistent economic theory in order to interpret any particular data. Of course, as we will see below, GDP statistics can also be abused by historians, economists, and others to draw incorrect conclusions.

A Spending-Centric View (C)

Although Keynes did not pen his General Theory and usher in the “Keynesian Revolution” until 1936, there was a potent faction that already shared his general ideas prior to his publication. These were the proto-Keynesian underconsumptionists whose main idea was that economic downturns were primarily due to “underconsumption” or lack of aggregate demand. This allegedly led to fewer purchases of final consumer goods, thus reducing the incomes of producers and leading to further economic decline, impoverished businesses, unemployment, lack of investment, and lack of purchasing power. Therefore, the task of the government in a downturn is to “stimulate investments and discourage savings, so that total spendings increase.”

Because of this fallacy—later unintentionally exacerbated by GDP—people have been led by the common, but fallacious, idea that “spending drives the economy.” This is a popular Keynesian illusion and it is pervasive. For example, it is often claimed that consumer spending accounts for some 70 percent of economic demand. According to Dr. Mark Skousen, GDP overlooks business-to-business (B2B) spending,

One of the major sources of this misconception is the way national income accounting is taught…. the textbooks focus on GDP as the macro indicator of the economic performance. And thus, the media is easily led to the misguided conclusion that consumer spending drives the economy.

Skousen recommends his General Output (GO) as a supplementary macroeconomic measure and argues that it demonstrates that business spending is actually the biggest sector of the account—accounting for some 60 percent of economic activity. That is not to deny that production has to be according to consumer demand nor that consumers are the ultimate “bosses” of the direction of production. Instead, it simply recognizes the importance of Say’s law, rightly understood, that one’s ability to demand goods on the market ultimately has to do with goods/services one is able to offer in exchange, not just the money spent. It is not consumer spending itself that drives the economy, but rather production and exchange. Without prior production, there is nothing to exchange and/or consume.

With such faulty presuppositions regarding the role of consumer spending, GDP helps further errors. Personal consumption expenditures (C) are a key part of the measure, but when spending declines, GDP declines, therefore, it could be concluded that boosting spending will boost GDP and economic health. The first part of the conclusion is true: spending will boost GDP, but not necessarily economic health. Further, it is one easy step to the next faulty conclusion: when consumer spending declines, GDP (assumed as economic health) can be boosted by government spending. Robert Higgs—one of the key Austrian authors on this topic, who developed Gross Domestic Private Product (GDPP)—writes, “The vulgar Keynesian focus on consumption unfortunately tempts politicians to approve ‘stimulus’ measures aimed at pumping up this part of total spending…”

Government Spending & Investment (G)

Mises—thinking along the same lines as Bastiat and Hazlitt—had the wisdom to look beyond the immediate, obvious (“seen”) economic effects of a policy, to trace through all the consequences, and take account of opportunity cost (what was foregone by an action). Further, Mises also made the crucial distinction between government and the private economy. He recognized that the nature of government meant that it was in a different category regarding spending, investment, and consumption. He wrote,

As against these popular fallacies there is need to emphasize the truism that a government can spend or invest only what it takes away from its citizens and that its additional spending and investment curtails the citizens’ spending and investment to the full extent of its quantity.

Mises recognized that a government can only “give” by first taking and that government spending is literally at the expense of the private economy. This is true through inflation, debt, and taxes, however, even more so through the “crowding out” effect of government action—the labor and resources the government “spends” (consumes) are now no longer available in the same way in the private economy. This was frankly acknowledged as a problem by the originator of GDP—Simon Kuznets.

Kuznets recognized two unsatisfactory options for counting government action in the economy: the cost principle (how much revenue the government spends) versus the payment principle (how much the government “earns” in taxes). He admitted, “The choice between the two principles is largely between two evils, for neither is adequate.” If we think carefully, we can see obvious problems with both of these options.

By simply looking at what government decides to pay for things (cost) overlooks that those activities are not priced on a free market and that governments do not operate on a profit-and-loss basis. On the other hand, by looking at how much people “pay” government for its “services” overlooks the obligatory nature of taxation and the disconnect between payment and service. Kuznets toyed with the concept of at least treating governmental activities as unproductive and valuing their services as zero, but rejected it. Kuznets wrote,

But the essential difficulty will remain, viz., governments (and related semipublic sectors) and the private business sectors (both firms and individuals) do not and cannot operate under the same rules, any more than do or can the business and what may roughly be called the family sectors. The difficulties in handling the latter are reduced by excluding it almost completely from national income; but national income includes both the private business and the public sectors. The fundamental difference in the principles on which these sectors operate means that some arbitrary decisions will always be called for in order to put the two together—by applying the private market or public economy base to both, or by devising some common denominator. (emphasis added)

These issues and Kuznets’s dissatisfaction notwithstanding, this led to the selection of the payment principle. However, a switch was made to the cost principle during WWII, against his objections. This meant that, as the government spent, GDP increased. This often led to equating government spending with economic growth and prosperity. For example, this helped contribute to the “wartime prosperity” myth and that WWII extracted the US from the Great Depression. Higgs showed that this statistic helped create an illusion (one that still remains to this day)—that WWII was prosperous because of GDP increases (caused by increases in G).

(Higgs, Regime Uncertainty, p. 565)

(Higgs, Regime Uncertainty, p. 566)

Following GDP, and assuming it equates to the health of an economy, we see that GDP was high during WWII, but when we disaggregate government spending (G)—which artificially boosts GDP at the expense of the private economy—we see that economic health and growth did not improve during WWII, let alone because of WWII. Therefore, GDP as a metric often misleads people to falsely equate GDP with economic health and government spending with economic growth.