While President Trump seesaws between punishing or not punishing Canada and Mexico with tariffs, he has shown no such hesitation when it comes to China. Upon returning to the Oval Office, he doubled the 10% tariff on Chinese exports to the United States. The People’s Republic retaliated with tariffs on a range of US agricultural products, with the latest People’s National Congress in Beijing warning of a “bitter” fight ahead.

That sounds like a script for a trade war, but it may not play out this way.

Chinese tech stocks have rallied sharply in recent days, and Beijing shows little inclination to escalate relentlessly in response. This is because both Washington and Beijing know well that the old bilateral China-US trade relationship is untenable. Under that arrangement, US consumers underwrote China’s industrial might at the expense of America’s domestic manufacturing sector. It was the product of a neoliberal consensus that has proved deeply unpopular with the working-class and lower-middle-class Americans who form the Trumpian GOP’s base.

In short, the old free-trade regime isn’t coming back, and both sides are making plans accordingly. Trump may reduce tariffs on Chinese goods in exchange for stronger action to curb illegal immigration and opioids, or other concessions. Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick said on 5 March, “I think [Trump’s] going to figure out, ‘you do more, and I’ll meet you in the middle some way’. And we’re probably going to be announcing that tomorrow”. Hong Kong’s tech stock index, which traded flat until just before Tuesday’s close, jumped 10% in the three sessions after Lutnick’s remarks came across the wire.

“There’ll be a little disturbance. But we’re okay with that. It won’t be much”, Trump said of the impact of tariffs in his address to a joint session of Congress. Contrary to the remonstrations of Lawrence Summers and other neoliberal economists, he well may be right.

Here’s a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the impact of tariffs: in December 2024, the American economy imported $250 billion worth of goods, while retailers sold $650 billion in goods. Imports are about 40% of retail sales. If the average tariff is 10%, and half of that 10% is absorbed by exporters to the United States, the resulting impact on the price level for imports goods would be 5%. In turn, 5% of the 40% import share in retail sales is 2%. Goods comprise roughly half of the Consumer Price Index, so the impact on overall inflation would be around 1%. (Of course, a great deal of imports are production inputs, rather than finished goods, but let’s assume that the cost is simply passed on to final consumers.)

That would be the “little disturbance” the President has mentioned. An average 10% tariff on $3 trillion a year of imports would yield about $300 billion in revenues, enough to put a meaningful dent into America’s $1.8 trillion budget deficit. This is the benign scenario.

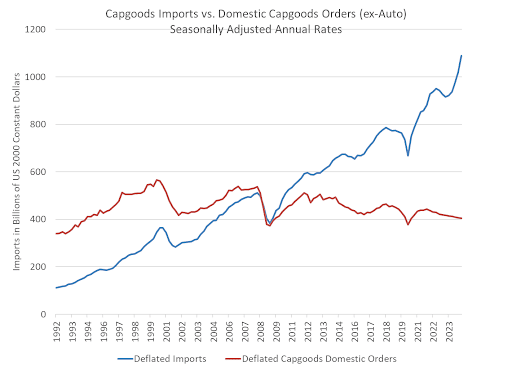

There may be some collateral damage, in particular to business investment. The United States now imports more capital goods than it produces at home, and investment in equipment fell sharply at the end of 2024. Higher prices for capital goods due to tariffs might suppress investment and, perversely, make the US more dependent on imported goods. The administration will do its best to strike a balance between structural change and short-term economic sensitivities.

Because so much of US manufacturing depends on foreign inputs, it will be hard for domestic manufacturers to replace imports with local production. If Trump ramps up the tariff to 25%, it would produce more than a little disturbance — perhaps a 5% increase in the average price of goods sold in the US — but a 10% rate is manageable. And there’s another factor working in Trump’s favour: foreign businesses may invest in the United States to avoid tariffs. Trump claimed in his speech to Congress that $1.7 trillion in foreign investment was already in the pipeline. That may be an optimistic estimate, but more foreign investment is a net positive for the US.

Still, there is reason to be anxious, and the White House will watch the impact of tariffs on the economy closely. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, a key member of the President’s inner circle, warned 25 February that the US had entered a “private-sector recession”. He added: “The previous administration’s over-reliance on excessive government spending and overbearing regulation left us with an economy that may have exhibited some reasonable metrics but ultimately was brittle underneath”.

Private investment began contracting in the last quarter of 2024. There are warning signs of economic weakness: the highest unemployment claims in two years and low employment growth in a private ADP survey; sagging consumer confidence according to University of Michigan and Conference Board surveys; and a sharp 0.9% fall in January retail sales.

“Working in Trump’s favour: foreign businesses may invest in the United States to avoid tariffs.”

Which brings us to China’s perspective. Chinese policy makers were initially hoping for a return to the 2020 “Phase One” deal, in which the Middle Kingdom agreed to buy an additional $200 billion worth of US products (though it fell short of that commitment during the Covid recession). Peking University’s Professor Yao Yang, a prominent Chinese commentator, told the Chinese news outlet Guancha: “We can also consider buying American oil and gas, especially natural gas. Our energy procurement also needs to be diversified, and we can import more agricultural products”.

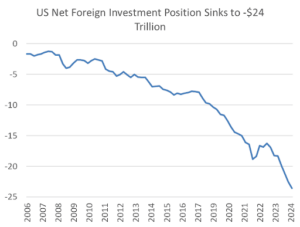

But turning the clock back to 2020 now seems improbable. Beijing reads the same numbers as Trump and his team, and Chinese officials know that Washington can’t continue to run a $1.2 trillion trade deficit forever. As of 2024, the United States had a net international investment position of negative $24 trillion. That’s the amount of assets the United States had to sell to finance the last 30 years of trade deficits. What can’t go on forever, won’t. Aware of US vulnerability on this count, Chinese officialdom has now set aside its “Phase One” hopes.

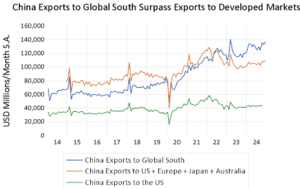

And China is prepared. The first Trump administration was a wake-up call for Beijing, and it spent the past eight years reimagining its place in the global economy. As a result, the world trade landscape has shifted dramatically: it isn’t so much that the United States has decoupled from China, as much as China that has decoupled from the United States. China’s exports to the America have shrunk, while its exports to the Global South have doubled; it now sells more to the Global South than to all developed markets combined. And it sourced 53% of last year’s soybean imports from Brazil, compared to 38% from the United States.

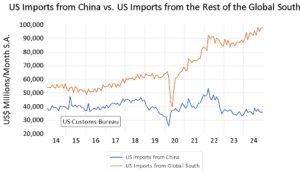

To be sure, China’s economic exposure to the US market — and America’s dependence on China for a wide range of products — is bigger than the bilateral trade data show. It’s true that US imports from China have fallen to less than $40 million a month, down from a 2022 peak of more than $50 million a month. However, US imports from the rest of the Global South have risen sharply. Crucially, much of US imports from Latin America and Asia are assembled in third countries using Chinese components, or come out of Chinese-owned factories.

For example, Vietnam — which is not subject to tariffs under the Trump regime — exports a quarter of its GDP to the United States, and imports the capital goods and production inputs to do this. There has been talk about imposing tariffs on Chinese content in imports from third countries, but that is impractical.

Bottom line: it simply isn’t in China’s interest to rock the boat. Beijing’s retaliatory tariffs on US agricultural products will shift China’s imports away from the United States and towards Brazil, which already provides China with more than half of its soybean imports. It will continue to shift manufacturing capacity to countries not subject to US tariffs, and its indirect exports to the US will compensate to some extent for the continuing decline of its direct exports.

While Uncle Sam and the Dragon look poised for a trade fight, their earlier decoupling, combined with the shifts in the global trade landscape, will likely avert the worst.